How Are Exoplanets Discovered? | Discover Magazine

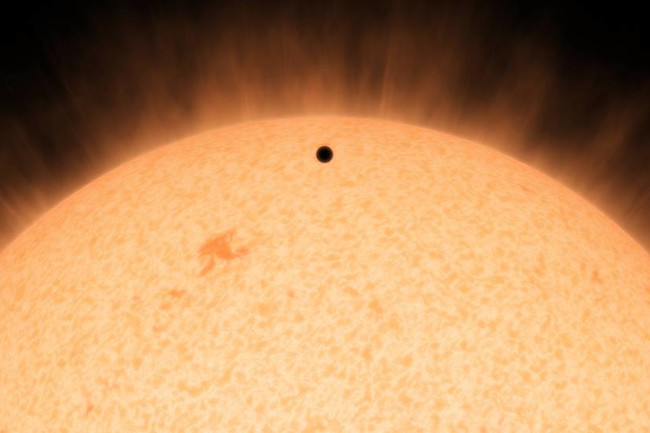

This artist’s principle reveals the silhouette of a rocky planet, dubbed High definition 219134b, transiting its star. (Graphic Credit score: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Exoplanets, by definition, exist outside our photo voltaic process, orbiting other stars. That indicates they are very considerably away. Telescopes, even top rated-notch ones like Hubble, can not image everything as modest as a planet outside our photo voltaic process. Even Neptune, in our personal photo voltaic process, is a blurry blue ball when considered from Earth’s orbit.

So planets outside our photo voltaic process are pretty much invisible. Even so, planets can and do influence their stars in measurable ways, and which is how astronomers obtain them.

The two most widely applied procedures are transits – the blinking technique – or Doppler shifting – the wobble technique.

When a planet orbits its star, the planet will sometimes cross concerning it and Earth. This crossing is known as a transit, and when it happens, the planet blocks a little bit of the star’s gentle. It may be effectively underneath one percent of the gentle, but which is enough for specific telescopes to evaluate. If that star is blinking in a common, cyclical pattern, that tells astronomers there is a planet circling it – as effectively as the dimension (width) of the planet and how significant its orbit is.

In the wobble technique, astronomers rely on the simple fact that just as stars tug on their planets to maintain them in orbit, planets also tug on their stars. So, as a planet circles, its star will wobble back and forth really a little bit. This wobble is usually as well modest to see in an image, but it does clearly show up as a wiggle in the spectrum, or coloration, of the star. Yet again, astronomers seem for a pattern to that wiggle, which tells them how significant a planet is and how considerably away it orbits.

Go through extra: