China’s Most Advanced Power-Grid Tech Is in Xinjiang, But Good Luck Trying to See It

Very last year I boarded a flight to China on a mission to report on an rising supergrid whose scale and scope remain unimaginable for grid operators everywhere else. Looking at China’s ultrahigh-voltage transmission energy technologies up close experienced been a longstanding dream for this incurable energy geek. Electrical power writers, myself incorporated, experienced coated China’s UHV program from the outside the house. This time, I’d been invited by the Point out Grid Corp. of China—the world’s premier utility by revenue and workforce and China’s UHV leader—to stage inside of its installations and study labs.

I the natural way desired to see Point out Grid’s most current and finest gear, and that meant heading to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region—the northwestern territory named for its Turkic Muslim ethnic group.

Xinjiang was the spot to go because its loaded coal, wind, and photo voltaic assets considerably exceed its strength requirements, and Point out Grid was making its premier UHV transmission challenge to date to export these riches. I desired to see the project’s converter station outside the house Xinjiang’s funds, Ürümqi, which was built to consider in alternating present-day from regional energy plants and spit out direct present-day at a blistering one,100 kilovolts—a third larger voltage than China’s earlier history-environment 800-kV converters. That DC voltage would help electricity from Xinjiang to journey as considerably as Shanghai—nearly one,000 kilometers farther than any other energy line in the world.

You can read all about the technologies behind Xinjiang’s one,100-kV UHV DC challenge in my new special report on its subsequent startup. And you can discover about the origins of Point out Grid’s UHV technologies and its battle to work the resulting UHV AC-DC energy grid in “China’s Formidable Prepare to Build the World’s Major Supergrid,” my aspect in IEEE Spectrum’s March problem.

Alas, I by no means did see the groundbreaking infrastructure in Xinjiang myself.

My earlier reporting in China had organized me for the normal language and cultural obstacles. But on this vacation, I encountered a complete new established of controls on speech and movement that threatened to constrain my work. As I got ready to journey to China last March, governing administration clampdowns against suspected separatists and extremists inside of the Uyghur community ended up drawing international criticism. Human legal rights teams and some Western governments named out a new stability regime in Xinjiang that incorporated “widespread use of arbitrary detention, technological surveillance, intensely armed street patrols, stability checkpoints and an array of intrusive guidelines violating human legal rights,” in accordance to Amnesty International [PDF].

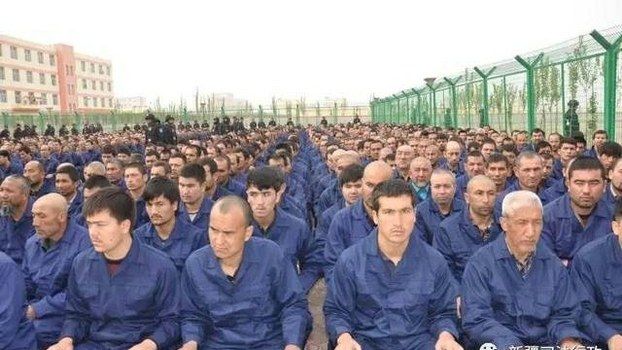

Criticism intensified when Radio Totally free Asia, a U.S. government–funded media outlet, claimed that one hundred twenty,000 Uyghurs ended up remaining held in political re-instruction camps in 1 Xinjiang district, and extra ended up remaining detained elsewhere. The scale reinforced arguments by China’s critics that its law enforcement crackdown amounted to discriminatory racial and spiritual profiling.

Xinjiang Judicial Authority by means of WeChat/Wikipedia

The initial indicator that my visit to Xinjiang could possibly fall through was a mysterious collection of lodge cancellations. I’d prepared a side vacation to see the ancient Silk Road metropolis of Turpan and its archaeological websites and Uyghur society. 1 7 days prior to my flight to Xinjiang, the on the net journey web site vacation.com notified me that my lodge reserving for Turpan experienced been canceled. When I tried out to make other bookings in Turpan, they ended up equally reversed.

Any hope of looking at Point out Grid’s building in Xinjiang finished two days right before my flight to China, when my hosts claimed that the territorial governing administration experienced imposed a twenty-day hold off to review my admissibility.

I regarded that the “delay” was a de facto rejection. Subsequent restriction and harassment of foreign journalists bound for Xinjiang suggest I got off light-weight. Formally, the only Chinese region that’s off-boundaries to journalists is Tibet—a plan that recently prompted U.S. journey limits on some Chinese officials. But many reporters also skilled “prohibited or restricted” accessibility in Xinjiang and other places deemed “sensitive,” according to a 2018 study by the Overseas Correspondents’ Club of China.

To deliver home the UHV story, I switched to Prepare B and established class for 1 of Point out Grid’s most recent 800-kV converter stations just southeast of Xinjiang in Gansu province. It was perfectly value the vacation. The Qilian Converter Station is named for the glacier-topped mountains close by. Since starting off up in 2017, it is been exporting gigawatts of energy captured from the robust and constant winds these mountains support make.

Visiting Gansu also gave me a taste of Uyghur lifestyle. In the oasis city of Dunhuang (Dukhan in Uyghur), I dined on lamb’s brain–an intensely loaded and disconcertingly sticky-easy pâté served in cranium. I also witnessed the surveillance point out that China is making outward from Xinjiang.

The photograph at the top rated, taken in a small alley in Dunhuang, displays 1 of the stability cameras that are now omnipresent in Xinjiang and paired with facial-recognition algorithms. According to the Washington Post’s former China bureau chief Simon Denyer, “Facial-recognition cameras [in Xinjiang] have grow to be ubiquitous at roadblocks, outside the house gasoline stations, airports, railway and bus stations, and at residential and university compounds and entrances to Muslim neighborhoods. DNA selection and iris scanning include additional levels of sophistication.”

Since my vacation in March 2018, there has been escalating recognition of the difficulties in Xinjiang. In August an qualified panel assembled by the United Nations Human Rights Council, citing “credible resources,” stated that China experienced interned extra than 1 million people today, turning Xinjiang into a “no legal rights zone” where Muslims ended up taken care of as “enemies of the Point out.” Panel member Gay McDougall, distinguished scholar-in-residence at Fordham University’s Leitner Center for International Legislation and Justice, explained authorities experienced criminalized common cultural procedures, like “daily greetings, possession of specific halal products, and escalating a comprehensive beard.”

Xinjiang is making information yet again this month ahead of the U.N. group’s future session, in which it will consider up a report on human legal rights in China. Previously this month, Turkey’s foreign ministry condemned what it called “the re-emergence of concentration camps in the 21st century.” Human legal rights teams and some governments are contacting for an international actuality-discovering mission.

For its portion, Xinjiang’s territorial government finally acknowledged the camps’ existence in October, describing them as “professional vocational education institutions.” A Chinese delegate to the U.N. Human Rights Council insisted the camps ended up wanted, “to secure the human legal rights of the majority of people today,” in accordance to Canada’s Globe and Mail. He added that Xinjiang’s detainees have “never thought that lifestyle could be so colourful and so meaningful,” right before concluding: “Xinjiang is a good spot. Welcome to Xinjiang.”

That is, as prolonged as you are not a Uyghur—or a journalist.